One of us recently spent some time researching some of the discount retailers “for fun”. Little did we know the whole dollar store industry is actually nuanced, and throughout the research process, also found out we didn’t know what the buck we were talking about (and maybe we still don’t – you be the judge!).

This write-up covers Dollar Tree (“DLTR”, or the “Company”), including its subsidiary Family Dollar and the ongoing battle with Dollar General.

Discount Retailer Industry Segment Overview

There are 4 primary discount retailing models: (1) mass merchandisers (Wal-Mart, Aldi, Kroger), (2) overstock/closeout (Big Lots, Overstock), (3) multi-price point (Dollar General, Family Dollar, Dollarama), and (4) single-price point (Dollar Tree, 99 Cents Only).

The larger overstock/closeout merchandisers have generally since moved from lower to higher-price point merchandise. We will focus on single, multi-price point and mass merchandisers.

Mass merchandisers typically operate larger stores, with Wal-Mart’s neighbourhood and discount stores averaging of 42k and 105k sqft, respectively. Due to these larger store sizes, they tend to be in relatively higher-density cities and provide a wide variety of consumable and other products.

Multi-price point discount retailers (“MPPs”) sell items typically priced <$10 and operate “small-box” stores generally ranging from ~7k – 12k sqft. MPPs can operate in rural towns with lower populations due to the smaller store sizes. Compared with mass merchandisers, MPP customer shopping trips are usually short and small but are made more frequently. MPPs are a volume-driven business, and customer traffic is driven by consumables products (particularly food/perishables); sales mix therefore tends to be heavily-weighted towards consumables. Since consumables (1) tend to be lower-margin products to retailers, (2) are required to drive customer traffic, and (3) make up a substantial portion of revenues, it is critical for MPPs to source low-cost consumable products.

Single-price point discount retailers (“SPPs”) sell items priced at or around $1. They share similar small-box store formats to MPPs, though sales are more evenly weighted between consumables and variety categories. SPPs cannot raise their product prices, and these stores also require high sales volumes and store traffic; customers make more “impulse” purchases at SPPs, and product SKUs frequently change. There is some overlap between MPPs and SPPs, as MPPs often have “$1 or less” sections, and SPPs have also had to increase the consumables sales mix over the last 2 decades to compete with MPPs.

Now this is all a bit abstract. Thankfully, of course, there’s a video on YouTube giving you a real live example of the dollar store enthusiast shopping experience!

Product Types and Supplier Relationships

Consumable products include food, health/beauty, and household cleaning supplies. To retailers, consumable products tend to be lower-margin but can branded by familiar third-parties (Coca-Cola, P&G, Hershey, etc) or private-label (Costco-Kirkland, Loblaw-President’s Choice, etc) – shoppers select consumables based on cost and brand recognition. Retailers generally use lower-margin food/perishable consumables to increase (1) store traffic and (2) average shopping cart value. Therefore, a large retailer that directly sources its own private-label consumables from a fragmented supplier base would likely have a cost advantage over another retailer that does not.

Variety and Seasonal products include toys, gifts, some houseware, and party/holiday items. In the context of Dollar Tree stores, DLTR sources its variety products from a fragmented supplier base that competes for its bulk purchase orders. These products therefore tend to be higher-margin relative to consumables. DLTR is an unusually large purchaser of <$1-price point items, and this results in: (1) DLTR’s variety product costs are lower relative to some larger non-SPPs, (2) DLTR has the bargaining power to modify products and customize packaging, and (3) suppliers frequently change as do the products, which keeps a continuously-changing inventory mix.

Dollar Tree before Family Dollar – History and Business Economics Evolution

DLTR was founded in 1986 as Only One Dollar, Inc., and initially began operations as a closeout toy merchandise store. In the early 1990s, the founding management team changed its strategy (1) from closeout merchandise to an SPP variety store format, and (2) to focus expansion on strip malls. In 1993 the company changed its name to Dollar Tree to reflect this new business model.

The founding management team’s idea actually came to them after seeing a dollar-store business go bankrupt, showing that something good can come out of something bad!

1990s – Dollar Tree’s Heydays

Throughout most of the 1990s, DLTR was extremely profitable and grew with minimal invested capital. Dollar Tree stores were typically (1) ~4k selling sqft large, and (2) located in strip malls anchored by strong mass merchandisers such as Wal-Mart and Target, which had similar target customers.

DLTR followed mass merchandisers to “piggyback” off the high foot-traffic these retailers naturally attracted (this sounds like cloning to us – why hire a bunch of marketing and real estate folks to do a ton of industry research when you can just follow the big players around? [We’re huge fans of cloning investments here at CVI and have put together an extensive article inspired by Mohnish Pabrai here - http://canadianvalueinvestors.squarespace.com/cloning-investments-101 ]

Strip mall locations typically have lower initial capital investment and operating costs relative to shopping centers, and the smaller Dollar Tree stores allowed DLTR to sign short-term initial leases (with a DLTR option to extend) enabling the Company to expand and test new markets with lower risk.

The 2000s – How To Grow Profits Unprofitably

From 1998 – 2007, Revenues/SqFt and Operating Income/SqFt declined by 37% and 59%, respectively. However, as DLTR grew Total Stores and Total SqFt by 1.7x and 5.8x, Revenues and Operating Income grew by 3x and 1.5x, respectively. During this period, DLTR’s average new store size approximately doubled to ~8-10k sqft by the early 2000s, by way of M&A and expanded stores. Although the Company generally posted positive same-store-sales (“SSS”) growth from 1998 – 2007, this was largely due to store expansions being included in SSS data.

The larger stores also represented a shift in the Dollar Tree business model. Although the original smaller stores generally had higher operating margins, the larger Dollar Tree stores (1) sold a higher portion of lower-margin consumables (+1,000 bps over the period), and (2) offered a wider selection of products, both of which DLTR believed (3) supported store traffic and sales volumes.

This deterioration in Dollar Tree’s economics is likely in part due to market share loss to mass merchandisers/MPPs. During this period, Wal-Mart and Dollar General both grew Revenues/SqFt by ~20% and ~11%, while growing total square footage by ~480MM and ~35MM, respectively.

Dollar Tree From 2008 Onwards: Back to The Past

2008 – 2014 saw a resurgence in Dollar Tree’s economics, likely driven by (1) DLTR’s addition of freezers/coolers in most of its stores, which introduced more food/perishable consumables that resulted in (2) increased sales and traffic, and a (3) positive operating leverage impact.

As DLTR remained an SPP, it would be an unusually large purchaser of these types of consumables (given the price point, they are typically in small packages), which likely helped its ability to compete with the MPPs.

In July 2015, DLTR acquired Family Dollar, an MPP, marking a material shift in strategy perhaps on the same scale as the founding team’s 1991 decision to transition from a closeout merchandise to an SPP. However, DLTR has since been struggling to turn around Family Dollar, particularly in the face of formidable competition from Dollar General.

In 2010 – 2011, several activist investors acquired 27% of Family Dollar, with Trian (8% shareholder) calling to take the company private - https://www.cnbc.com/id/38446157 . Ultimately, Family Dollar entered into a 2-year standstill agreement to give the company time to close the performance gap against Dollar General.

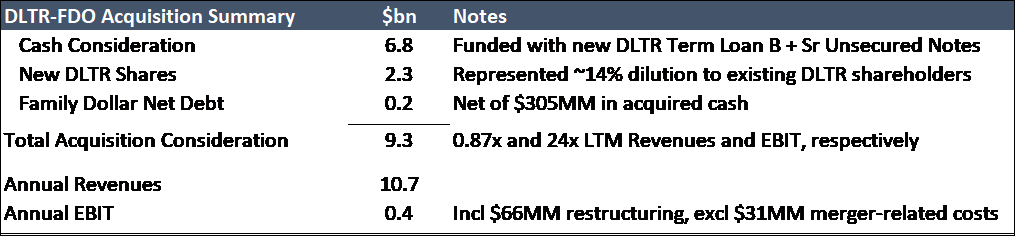

Unfortunately, Family Dollar did not materially improve operations. Round two of the activists came in 2014 where Carl Icahn called for an immediate sale. A bidding war ensued between Dollar General and DLTR, and that eventually led to the sale to DLTR for $9.3bn / 24x EBIT.

Family Dollar vs Dollar General – Business Economics

Not all dollar stores are created equal. Although Family Dollar and Dollar General both need a high consumables inventory mix to drive traffic into their stores and increase sales of other higher-margin products, they approached this issue in distinct ways: Family Dollar signed a 6-year contract in 2012 with a third-party supplier (McLane, a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary) for many food/perishables consumables, while Dollar General (1) procured more volume but less variety of SKUs per product category, and (2) kept a more fragmented supplier base particularly for its private label products as shown below. [Note: McLane is another interesting company – they help keep things moving out of sight of consumers - https://www.mclaneco.com/content/mclaneco/en/about.html#history ]

Although McLane only makes a ~0.6% pre-tax margin, this may be enough to contribute to Family Dollar’s cost disadvantage versus Dollar General, which has relatively stronger bargaining power against its diversified private label consumables suppliers. Family Dollar may also have a supplier-dependent relationship with McLane, making a quick switch difficult.

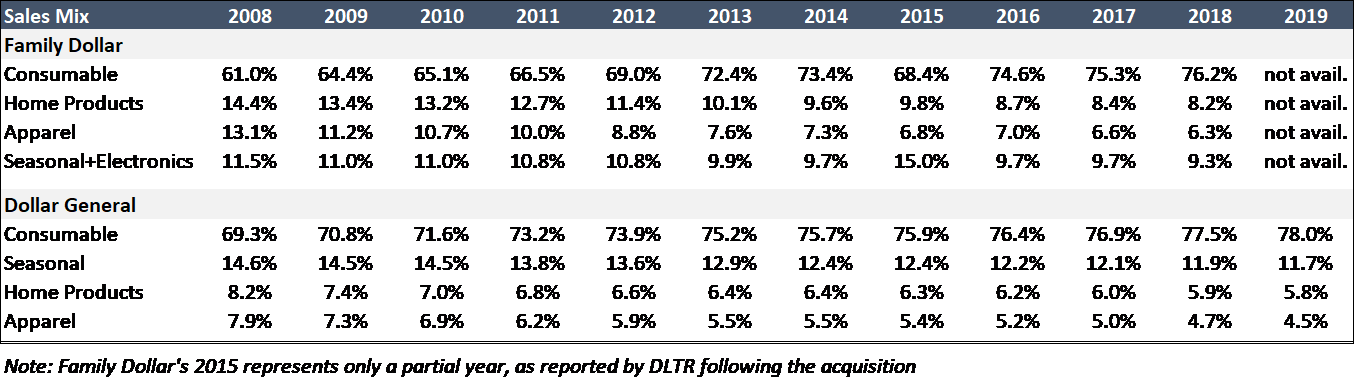

Family Dollar’s consumables cost disadvantage means it cannot offer as many inexpensive consumables, which is a key driver to increasing store traffic. This is evident in Family Dollar’s lower Revenue/SqFt and Operating Income/SqFt, despite the fact it has a relatively lower percentage of total sales from lower-margin consumables as shown in the table below.

Good Bank-Bad Bank Good Retailer-Bad Retailer (also: a case study on why you should not listen to M&A bankers)

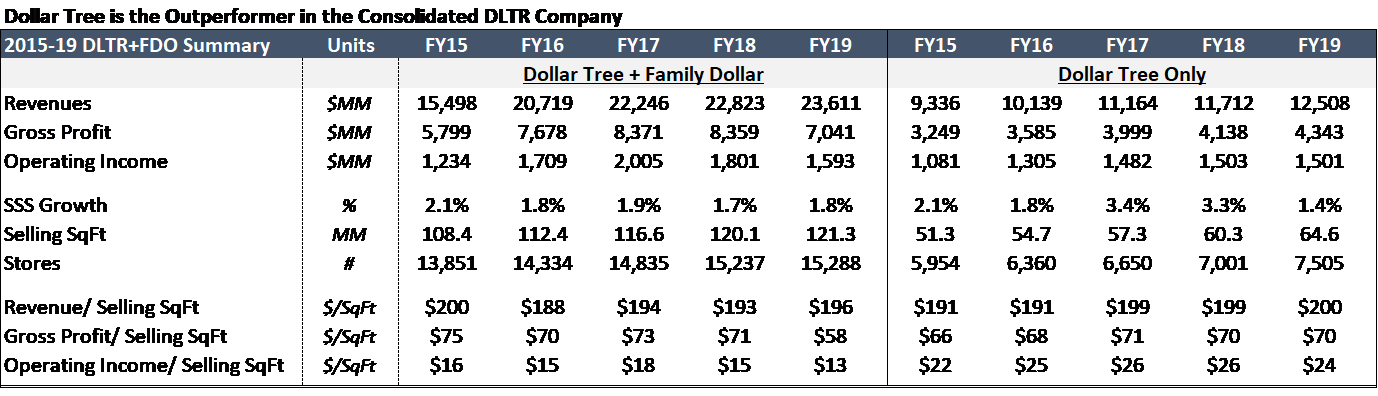

It is hard to overstate how Family Dollar has been a drag on the overall DLTR results…but we think this table pretty much shows it! This is also a great example of how acquisitions don’t always work out, despite what your friendly neighbourhood M&A advisor might say.

A Forgotten Part of the Business: Infrastructure

~80% of a typical SPP/MPP’s capital requirements would be leasehold improvements and net working capital. However, DLTR (and Family Dollar) appears to have historically underinvested in its distribution center infrastructure compared with Dollar General, which has spent more per SqFt on distribution centers that are at least ~30-40% more productive (as measured by total system sales capacity / total infrastructure SqFt).

Inefficient distribution infrastructure may be another reason for Family Dollar’s cost disadvantage and interestingly, DLTR has spent a lot more on its distribution centers in the last few years. However, to match what Dollar General has spent per SqFt, DLTR would likely have to spend upwards of $1bn just on its distribution centers – yikes! It may very well be worth doing this in the very near-term, though.

With Oil & Gas companies, we have generally noticed that lower-cost companies do not take shortcuts when it comes to investing in their owned infrastructure (gas plants, etc). Similarly, we figure this applies to retailing as well.

So Where Does This All Leave Us?

Well, as it relates to DLTR…it goes in the too-hard pile for us, but we wish you luck! At the current market value, it does not strike us as particularly expensive or cheap, and any material upside will depend on their successful turnaround (or sale at a lofty valuation) of Family Dollar. We think Family Dollar’s competitor Dollar General is well-run, and as Buffett has said and witnessed many times, turnarounds seldom turn. We wish all the best to DLTR, but we did appreciate learning about its interesting history and its competitors!